Ophanim

The entirety of Danival's existence came to an end in a cold, poorly lit room with a mold stain next to the power outlet. Danival and his companions wore thin clinic robes. Strapped to flimsy lawn chairs. Poked with tubes that monitored fluids. They would lie there silently. The helmets on their heads would whir, indicator lights would flash. The cables from the helmets lead to a central pillar in the room. From floor to ceiling, it was too wide to wrap your arms around. It was a single computer. Some of the participants might remember their body told them there was pain, that they had been crushed or peeled apart by the sinew of each muscle. Most would not remember a thing. Only the black stillness of their dead minds reflected the death which filled the room.

His heart stopped pumping. The flow of oxygen in his veins slowed to a crawl. As his lips turned purple, his body jerked, heaved to fill lungs with air. As if to copy the body, the brain lurched again. Every node with the capability to muster a sound came together as one unified shout. A roar to the rest of the body, to his consciousness, to WAKE UP! All of the colors expanded and filled every lobe. They overprocessed so hard that his eyes received white. A white so intense and void of any impurity that it would hurt had his nerves not already been burning, reaching out to grasp for their neighbor and latch onto something familiar, something home, something that would mean they would make it into tomorrow. When he died, his mind faded into obscurity with the blossoming of the universe. An amalgamation of everything his minuscule, meat sack of a brain could ever hope to comprehend or had experienced through the blip of a couple decades.

~

He remembered a yellow doll. He sat next to the living room tatami table. He had just become too big to crawl underneath it. The doll fit. His mother smacked him on the head with a soupy ladle. He remembered it, but he did not grow up with a table like that.

It was there when he had his first kiss. Maria Mei Lao Hernandez was at his house to pick up an incorrectly delivered package. Danival happened to be in the kitchen when she rang the doorbell. After he let her in, he noticed the doll sitting on the counter. Next to the package. He had a crush on her. He didn’t want her to know he kept a girl’s toy. He slipped from a combination of nervousness and that awkward growth stage that made it feel like you were stuck in clown shoes. He knocked the doll off the counter. She grabbed his arm under the elbow. She caught the doll. She held him steady. Her grip was firm. It embarrassed him how strong she was, but he didn't want her to let go. She helped him up. She inspected the doll and exclaimed how beautiful it was. She smelled like caramel and lychee. Their faces were close, so Danival took the chance and went for the kiss. He missed and pecked the corner of her nose. Her face flushed red. She smiled. “Well, I’ll bring this to my mom.” She said and rushed out the door.

The doll was his mother’s. She used to tell him stories about how her father, his grandfather, gave it to her at the crowded docks of Ping She. The social worker, a muscled man, held her in his huge arms against the crowd. She cried as Grandfather pulled her tiny fingers from his face, from his ears, from the collar of his shirt, and replaced them with the toy. “Keep this with you,” he had said. “It will guide me to you, Little Star.” The crowd crashed in. A flood of screaming, sharp-toothed faces. She cried and screamed, but the crowd screamed louder. The social worker loaded her onto the boat. It was a small ship. It was dented and cracked and rusted and shook with his weight. It broke from the dock, and she could not see her father in the wall of bodies receding on the shoreline.

She held the doll close to her as she was transferred with the other refugees to the encampment. She fought the children who tried to take the doll from her. She would not let them put it in her luggage when they boarded the plane from China to Brazil. She always carried it as she walked to school and visited the refugee center’s Family Connection Office every Sunday. She made sure it fit in her bag as she became an adult and went to job interviews. She even held the doll when she gave birth to her two children. Somehow, Danival couldn’t remember seeing the thing in a single family photo or snapshot. But she did teach him how to brush the doll’s hair and clean smudges on its skin without warping the designs. She taught him to sew so he could repair the clothes if they were damaged. As a child, she brought him to the FCO and showed him how to present the doll to the scanners. He watched the results come up negative, flashing “unmatched” green, every week. After all this time, her father, Danival’s grandfather, had never scanned the matching device.

No, that wasn’t right. Danival didn’t know his mom’s birthday, but he knew she wasn’t an immigrant. His great-grandmother was a baby when that side of the family moved to Brazil. Right? Through whose eyes had he seen all that? Who was the woman who wasn’t his mom?

The white flash of light.

Danival was back in university. His coffee mug had the face of the doll, no, it was the doll, no, it was the coffee mug. It was cold now. He would throw it out. The university board was telling him that he didn’t have enough passing credits to remain enrolled. Danival said he understood but only needed one more class to fix his GPA. The dean pushed their face close to the camera and opened their mouth. Danival heard the dean’s voice as his own: “SO YOU KNEW YOU WOULD NOT HOLD AN ACCEPTABLE GPA?” He responded, Yes. “THEN YOU FORFEIT YOUR LIVING ARRANGEMENT.” And the line had cut.

The doll was in his dorm room, but he could not open the door. His keypass had been reprogrammed. His items were thrown away.

He had lost the line to his grandfather, to his homeland, to the effort and care his mother had put into keeping the doll pristine. It was thrown away because he slept through morning classes and refused to study, is what his mother said when he told her. She cried and said she was disappointed. It made him want to cry, but she wouldn’t allow it. His mistake was her grief, it was her responsibility. The identity badge in the doll was burning in a reactor somewhere. Now she had to face the fact that her father died so many years ago on the shores of Ping She or starving in a food riot or dehydrated during a heatstorm. Her tears flooded the room into an ocean. He had no boat, so he slipped into the salty tear water and drowned.

He died.

~

Danival’s mind woke to pain smothering his body and an overwhelming feeling of shame he couldn’t pinpoint. He couldn’t see yet, so he squirmed in the darkness with his agony and embarrassment. His cold limbs tingled as the blood started to flow. A technician pulled off the helmet abruptly. His head dropped to the hard surface of the seat. He’d be painfully aware soon of where the helmet dug into the arch of his nose and pinned his ears.

Steadily, his vision returned. A small circle first, grayscale. Amorphous red, green, blue circles ate away at the dark perimeter. With each heartbeat, the circle would expand. Danival looked at the ceiling because that was all he could.

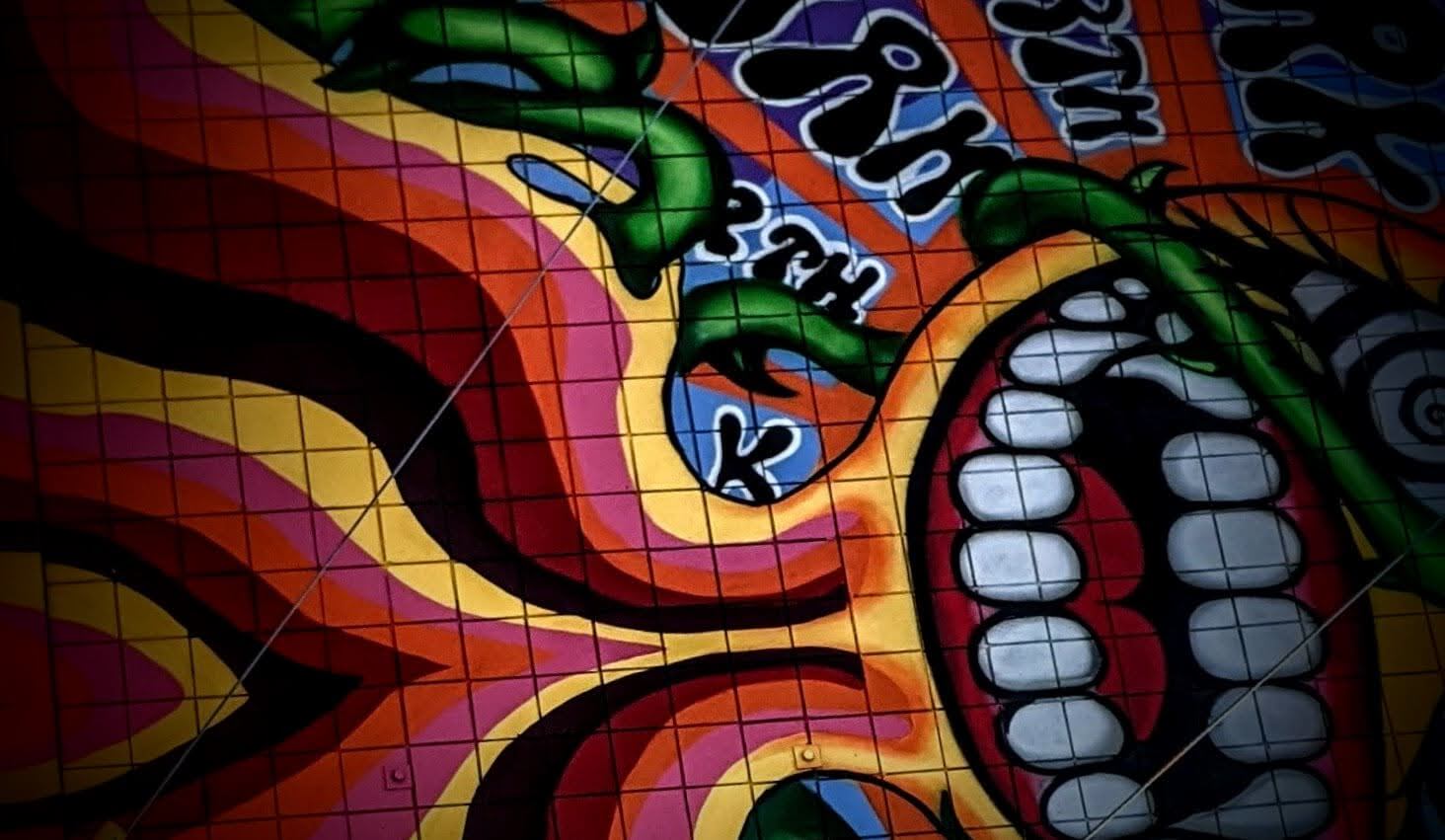

It was a laser printed mural to look like a grand oil painting layered and cracked over time. The perspective was warped so that it appeared as an encompassing dome. Even before the procedure, before his mind was at hangover-speed, it made him feel nauseous. The part of him that knew the room was a small cube fought with the part that could not escape the optical illusion. He remembered a field trip to a cathedral and how his neck hurt from looking straight up so long. In a moment of confusion, he thought about holding a yellow doll.

The scene was a mix of elements pulled from a waking dream. Cherubs and snakes danced along the boundaries of clouds and trees. The first color he could see was the orange cherub cheeks.

Danival’s eyes caught a pattern he couldn’t shake. He thought it was the cracks at first, but realized it wasn’t random: Eyes lining the edge of a disc, unbroken by any “flaws” in the printing. Men and women, with long, faded green and black robes, prayed around the disc. Their hands, in symbolic gestures, held modern devices. Each eye, which followed down the infinite horizon of the thing’s shape, was pointed toward a different character across the entire mural. He had never noticed it before and thought maybe they recently changed the mural. He also considered he just wasn’t observant. That was correct. The angel creature there held him with its infinite eyes. He took in the way the characters seemed to speak to it. It would process all of those messages, then point them out in shy winks or hard glares to anyone who happened to make eye contact with it or caught it in their peripheral. Danival shut his eyes tight. He fought back tears and bile.

An attendant leaned over Danival with a tray of tea and a few silicone shot glasses. He reached for one before the attendant could introduce the liquids, shot down the cup of the electrolytic mix, and grabbed a second before the attendant walked away. The attendant watched Danival throw back the second cup and quickly escaped before he grabbed a third. Another attendant would be over soon to help with the IVs.